Trigeminal nerve

| Nerve: Trigeminal nerve | |

|---|---|

|

|

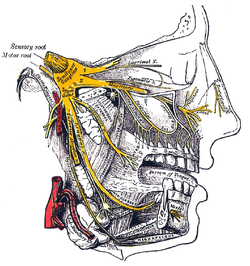

| Trigeminal nerve, shown in yellow. | |

|

|

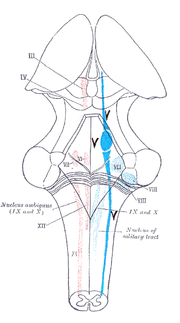

| Inferior view of the human brain, with the cranial nerves labelled. | |

| Latin | nervus trigeminus |

| Gray's | subject #200 886 |

| To | ophthalmic nerve maxillary nerve mandibular nerve |

| MeSH | Trigeminal+Nerve |

| Cranial Nerves |

|---|

| CN 0 - Cranial nerve zero |

| CN I - Olfactory |

| CN II - Optic |

| CN III - Oculomotor |

| CN IV - Trochlear |

| CN V - Trigeminal |

| CN VI - Abducens |

| CN VII - Facial |

| CN VIII - Vestibulocochlear |

| CN IX - Glossopharyngeal |

| CN X - Vagus |

| CN XI - Accessory |

| CN XII - Hypoglossal |

The trigeminal nerve (the fifth cranial nerve, also called the fifth nerve, or simply CNV or CN5) is responsible for sensation in the face. Sensory information from the face and body is processed by parallel pathways in the central nervous system.

The fifth nerve is primarily a sensory nerve, but it also has certain motor functions (biting, chewing, and swallowing). These are discussed separately.

Contents |

Function

The sensory function of the trigeminal nerve is to provide the tactile, proprioceptive, and nociceptive afference of the face and mouth. The posterior scalp and the neck are innervated by C2-C3, not by the trigeminal nerve.

The motor function activates the muscles of mastication, the tensor tympani, tensor veli palatini, mylohyoid, and anterior belly of the digastric.

Peripheral anatomy

The trigeminal nerve is the largest of the cranial nerves. Its name ("trigeminal" = tri- or three, and -geminus or twin, or thrice twinned ) derives from the fact that each nerve [ one on each side of the pons ] has three major branches: the ophthalmic nerve (V1), the maxillary nerve (V2), and the mandibular nerve (V3). The ophthalmic and maxillary nerves are purely sensory. The mandibular nerve has both sensory and motor functions.

The three branches converge on the trigeminal ganglion (also called the semilunar ganglion or gasserian ganglion), that is located within Meckel's cave, and contains the cell bodies of incoming sensory nerve fibers. The trigeminal ganglion is analogous to the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord, which contain the cell bodies of incoming sensory fibers from the rest of the body.

From the trigeminal ganglion, a single large sensory root enters the brainstem at the level of the pons. Immediately adjacent to the sensory root, a smaller motor root emerges from the pons at the same level.

Motor fibers pass through the trigeminal ganglion on their way to peripheral muscles, but their cell bodies are located in the nucleus of the fifth nerve, deep within the pons. Motor fibers of the eye are distributed (together with sensory fibers) in branches of the mandibular nerve.

The areas of cutaneous distribution (dermatomes) of the three branches of the trigeminal nerve have sharp borders with relatively little overlap (unlike dermatomes in the rest of the body, which show considerable overlap). Injection of local anesthetics such as lidocaine results in the complete loss of sensation from well-defined areas of the face and mouth. For example, the teeth on one side of the jaw can be numbed by injecting the mandibular nerve.

Sensory branches of the trigeminal nerve

The ophthalmic, maxillary and mandibular branches leave the skull through three separate foramina: the superior orbital fissure, the foramen rotundum and the foramen ovale. The mnemonic standing room only can be used to remember that V1 passes through the superior orbital fissure, V2 through the foramen rotundum, and V3 through the foramen ovale.[1]

- The ophthalmic nerve carries sensory information from the scalp and forehead, the upper eyelid, the conjunctiva and cornea of the eye, the nose (including the tip of the nose, except alae nasi), the nasal mucosa, the frontal sinuses, and parts of the meninges (the dura and blood vessels).

- The maxillary nerve carries sensory information from the lower eyelid and cheek, the nares and upper lip, the upper teeth and gums, the nasal mucosa, the palate and roof of the pharynx, the maxillary, ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses, and parts of the meninges.

- The mandibular nerve carries sensory information from the lower lip, the lower teeth and gums, the chin and jaw (except the angle of the jaw, which is supplied by C2-C3), parts of the external ear, and parts of the meninges.

-

- The mandibular nerve carries touch/position and pain/temperature sensation from the mouth. It does not carry taste sensation (chorda tympani is responsible for taste), but one of its branches, the lingual nerve carries multiple types of nerve fibers that do not originate in the mandibular nerve.

Motor branches of the trigeminal nerve

Motor branches of the trigeminal nerve are distributed in the mandibular nerve. These fibers originate in the motor nucleus of the fifth nerve, which is located near the main trigeminal nucleus in the pons. Motor nerves are functionally quite different from sensory nerves, and their association in the peripheral branches of the mandibular nerve is more a matter of convenience than of necessity.

In classical anatomy, the trigeminal nerve is said to have general somatic afferent (sensory) components, as well as special visceral efferent (motor) components. The motor branches of the trigeminal nerve control the movement of eight muscles, including the four muscles of mastication.

- Muscles of mastication

-

-

- masseter

- temporalis

- medial pterygoid

- lateral pterygoid

-

- Other

-

-

- tensor veli palatini

- mylohyoid

- anterior belly of digastric

- tensor tympani

-

With the exception of tensor tympani, all of these muscles are involved in biting, chewing and swallowing. All have bilateral cortical representation. A central lesion (e.g., a stroke), no matter how large, is unlikely to produce any observable deficit. However, injury to the peripheral nerve can cause paralysis of muscles on one side of the jaw. The jaw deviates to the paralyzed side when it opens.the reason is lower motor neuron paralysis of nerve causes loss of activity, where as upper motor neuron as it has bilateral even though it has damage in one side of cortex the other side helps in function as lower motor neuron is intact.

Central anatomy

The fifth nerve is primarily a sensory nerve. The anatomy of sensation in the face and mouth is the subject of the remainder of this article. Background information on sensation is reviewed, followed by a summary of central sensory pathways. The central anatomy of the fifth nerve is then discussed in detail.

Sensation

There are two basic types of sensation: touch/position and pain/temperature. They are distinguished, roughly speaking, by the fact that touch/position input comes to attention immediately, whereas pain/temperature input reaches the level of consciousness only after a perceptible delay. Think of stepping on a pin. There is immediate awareness of stepping on something, but it takes a moment before it starts to hurt.

In general, touch/position information is carried by myelinated (fast-conducting) nerve fibers, whereas pain/temperature information is carried by unmyelinated (slow-conducting) nerve fibers. The primary sensory receptors for touch/position (Meissner’s corpuscles, Merkel's receptors, Pacinian corpuscles, Ruffini’s corpuscles, hair receptors, muscle spindle organs, Golgi tendon organs) are structurally more complex than the primitive receptors for pain/temperature, which are bare nerve endings.

The term "sensation", as used in this article, refers to the conscious perception of touch/position and pain/temperature information. It does not refer to the so-called "special senses" (smell, sight, taste, hearing and balance), which are processed by different cranial nerves and sent to the cerebral cortex through different pathways. The perception of magnetic fields, electrical fields, low-frequency vibrations and infrared radiation by certain nonhuman vertebrates is processed by the equivalent of the fifth cranial nerve in these animals.

The term "touch", as used in this article, refers to the perception of detailed, localized tactile information, such as two-point discrimination (the difference between touching one point and two closely-spaced points) or the difference between grades of sandpaper (coarse, medium and fine). People that lack touch/position perception can still "feel" the surface of their bodies, and can therefore perceive "touch" in a crude, yes-or-no way, but they lack the rich perceptual detail that we normally experience.

The term "position", as used in this article, refers to conscious proprioception. Proprioceptors (muscle spindle organs and Golgi tendon organs) provide information about joint position and muscle movement. Much of this information is processed at an unconscious level (mainly by the cerebellum and the vestibular nuclei). However, some of this information is available at a conscious level.

The two types of sensation in humans, touch/position and pain/temperature, are processed by different pathways in the central nervous system. The distinction is hard-wired, and it is maintained all the way to the cerebral cortex. Within the cerebral cortex, sensations are further hard-wired to (associated with) other cortical areas.

Sensory pathways

Sensory pathways from the periphery to the cortex are summarized below. There are separate pathways for touch/position sensation and pain/temperature sensation. All sensory information is sent to specific nuclei in the thalamus. Thalamic nuclei, in turn, send information to specific areas in the cerebral cortex.

Each pathway consists of three bundles of nerve fibers, connected together in series:

It is noteworthy that the secondary neurons in each pathway decussate (cross to the other side of the spinal cord or brainstem). The reason for this is because initially Spinal Cord forms segmentally. Later on, decussated fibres reach and connect these segments with the Higher Centres. The main reason for Decussation is that optic chiasma occurs(Nasal fibres of the Optic Nerve cross so each cerebral hemisphere receives the contralateral vision) and to keep interneuronal connections short(responsible for processing of information) all sensory and motor pathways converge and diverge respectively to the contralateral hemisphere.(Courtesy H. Balram Krishna, excerpt from Cunningham's Manual of Practical Anatomy)

Sensory pathways are often depicted as chains of individual neurons connected in series. This is an oversimplification. Sensory information is processed and modified at each level in the chain by interneurons and by input from other areas of the nervous system. For example, cells in the main trigeminal nucleus (“Main V” in the diagram) receive input (not shown) from the reticular formation and from the cerebral cortex. This information contributes to the final output of the cells in Main V to the thalamus.

Touch/position information from the body is carried to the thalamus by the medial lemniscus; touch/position information from the face is carried to the thalamus by the trigeminal lemniscus. Pain/temperature information from the body is carried to the thalamus by the spinothalamic tract; pain/temperature information from the face is carried to the thalamus by the trigeminothalamic tract (also called the quintothalamic tract).

Pathways for touch/position sensation from the face and body merge together in the brainstem. A single touch/position sensory map of the entire body is projected onto the thalamus. Likewise, pathways for pain/temperature sensation from the face and body merge together in the brainstem. A single pain/temperature sensory map of the entire body is projected onto the thalamus.

From the thalamus, touch/position and pain/temperature information is projected onto various areas of the cerebral cortex. Exactly where, when, and how this information becomes conscious is entirely beyond our understanding at the present time. The explanation of consciousness is one of the great unsolved mysteries in science.

The details of the pathways connecting the lower body to the cerebral cortex are beyond the scope of this article. The details of the pathways connecting the face and mouth to the cerebral cortex are discussed below.

Trigeminal nucleus

It is not widely appreciated that all sensory information from the face (all touch/position information and all pain/temperature information) is sent to the trigeminal nucleus. In classical anatomy, most sensory information from the face is carried by the fifth nerve, but sensation from certain parts of the mouth, certain parts of the ear and certain parts of the meninges is carried by “general somatic afferent” fibers in cranial nerves VII (the facial nerve), IX (the glossopharyngeal nerve) and X (the vagus nerve).

Without exception, however, all sensory fibers from these nerves terminate in the trigeminal nucleus. On entering the brainstem, sensory fibers from V, VII, IX, and X are sorted out and sent to the trigeminal nucleus, which thus contains a complete sensory map of the face and mouth. The spinal counterparts of the trigeminal nucleus (cells in the dorsal horn and dorsal column nuclei of the spinal cord) contain a complete sensory map of the rest of the body.

The trigeminal nucleus extends throughout the entire brainstem, from the midbrain to the medulla, and continues into the cervical cord, where it merges with the dorsal horn cells of the spinal cord. The nucleus is divided anatomically into three parts, visible in microscopic sections of the brainstem. From caudal to rostral (i.e., going up from the medulla to the midbrain) they are the spinal trigeminal nucleus, the main trigeminal nucleus, and the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus.

The three parts of the trigeminal nucleus receive different types of sensory information. The spinal trigeminal nucleus receives pain/temperature fibers. The main trigeminal nucleus receives touch/position fibers. The mesencephalic nucleus receives proprioceptor and mechanoreceptor fibers from the jaws and teeth.

Spinal trigeminal nucleus

The spinal trigeminal nucleus represents pain/temperature sensation from the face. Pain/temperature fibers from peripheral nociceptors are carried in cranial nerves V, VII, IX, and X. On entering the brainstem, sensory fibers are grouped together and sent to the spinal trigeminal nucleus. This bundle of incoming fibers can be identified in cross sections of the pons and medulla as the spinal tract of the trigeminal nucleus, which parallels the spinal trigeminal nucleus itself. The spinal tract of V is analogous to, and continuous with, Lissauer’s tract in the spinal cord.

The spinal trigeminal nucleus contains a pain/temperature sensory map of the face and mouth. From the spinal trigeminal nucleus, secondary fibers cross the midline and ascend in the trigeminothalamic tract to the contralateral thalamus. The trigeminothalamic tract runs parallel to the spinothalamic tract, which carries pain/temperature information from the rest of the body. Pain/temperature fibers are sent to multiple thalamic nuclei. As discussed below, the central processing of pain/temperature information is markedly different from the central processing of touch/position information.

Somatotopic representation

Exactly how pain/temperature fibers from the face are distributed to the spinal trigeminal nucleus has been a subject of considerable controversy. The present understanding is that all pain/temperature information from all areas of the human body is represented (in the spinal cord and brainstem) in an ascending, caudal-to-rostral fashion. Information from the lower extremities is represented in the lumbar cord. Information from the upper extremities is represented in the thoracic cord. Information from the neck and the back of the head is represented in the cervical cord. Information from the face and mouth is represented in the spinal trigeminal nucleus. [

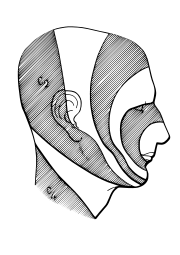

Within the spinal trigeminal nucleus, information is represented in an onion skin fashion. The lowest levels of the nucleus (in the upper cervical cord and lower medulla) represent peripheral areas of the face (the scalp, ears and chin). Higher levels (in the upper medulla) represent more central areas (nose, cheeks, lips). The highest levels (in the pons) represent the mouth, teeth, and pharyngeal cavity.

The onion skin distribution is entirely different from the dermatome distribution of the peripheral branches of the fifth nerve. Lesions that destroy lower areas of the spinal trigeminal nucleus (but which spare higher areas) preserve pain/temperature sensation in the nose (V1), upper lip (V2) and mouth (V3) while removing pain/temperature sensation from the forehead (V1), cheeks (V2) and chin (V3). Analgesia in this distribution is “nonphysiologic” in the traditional sense, because it crosses over several dermatomes. Nevertheless, analgesia in exactly this distribution is found in humans after surgical sectioning of the spinal tract of the trigeminal nucleus.

The spinal trigeminal nucleus sends pain/temperature information to the thalamus. It also sends information to the mesencephalon and the reticular formation of the brainstem. The latter pathways are analogous to the spinomesencephalic and spinoreticular tracts of spinal cord, which send pain/temperature information from the rest of the body to the same areas. The mesencephalon modulates painful input before it reaches the level of consciousness. The reticular formation is responsible for the automatic (unconscious) orientation of the body to painful stimuli.

Main trigeminal nucleus

The main trigeminal nucleus represents touch/position sensation from the face. It is located in the pons, close to the entry site of the fifth nerve. Fibers carrying carry touch/position information from the face and mouth (via cranial nerves V, VII, IX, and X) are sent to the main trigeminal nucleus when they enter the brainstem.

The main trigeminal nucleus contains a touch/position sensory map of the face and mouth, just as the spinal trigeminal nucleus contains a complete pain/temperature map. The main nucleus is analogous to the dorsal column nuclei (the gracile and cuneate nuclei) of the spinal cord, which contain a touch/position map of the rest of the body.

From the main trigeminal nucleus, secondary fibers cross the midline and ascend in the trigeminal lemniscus to the contralateral thalamus. The trigeminal lemniscus runs parallel to the medial leminscus, which carries touch/position information from the rest of the body to the thalamus.

Some sensory information from the teeth and jaws is sent from the main trigeminal nucleus to the ipsilateral thalamus, via the small dorsal trigeminal tract. Thus touch/position information from the teeth and jaws is represented bilaterally in the thalamus (and hence in the cortex). The reason for this special processing is discussed below.

Mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus

The mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus is not really a “nucleus.” Rather, it is a sensory ganglion (like the trigeminal ganglion) that happens to be imbedded in the brainstem. The mesencephalic “nucleus” is the sole exception to the general rule that sensory information passes through peripheral sensory ganglia before entering the central nervous system.

Only certain types of sensory fibers have cell bodies in the mesencephalic nucleus: proprioceptor fibers from the jaw and mechanoreceptor fibers from the teeth. Some of these incoming fibers go to the motor nucleus of V, thus entirely bypassing the pathways for conscious perception. The jaw jerk reflex is an example. Tapping the jaw elicits a reflex closure of the jaw, in exactly the same way that tapping the knee elicits a reflex kick of the lower leg. Other incoming fibers from the teeth and jaws go to the main nucleus of V. As noted above, this information is projected bilaterally to the thalamus. It is available for conscious perception.

Activities like biting, chewing and swallowing require symmetrical, simultaneous coordination of both sides of the body. They are essentially automatic activities, to which we pay little conscious attention. They involve a sensory component (feedback about touch/position) that is processed at a largely unconscious level.

The unusual anatomy of “mesencephalic V” has been found in all vertebrates, with the exception of lampreys and hagfishes. Lampreys and hagfishes are the only vertebrates without jaws. It is evident, therefore, that information about biting, chewing and swallowing is singled out for special processing in the vertebrate brainstem, specifically in the mesencephalic nucleus.

Lampreys and hagfishes have cells in their brainstems that can be identified as the evoutionary precursors of the mesencephalic nucleus. These “internal ganglion” cells were discovered in the latter part of the 19th century by a young medical student named Sigmund Freud.[2]

Pathways to the thalamus and the cortex

We have defined sensation as the conscious perception of touch/proprioception and pain/temperature information. With the sole exception of smell, all sensory input (touch/position, pain/temperature, sight, taste, hearing, and balance) is sent to the thalamus before being sent to the cortex.

The thalamus is anatomically subdivided into a number of separate nuclei. The thalamic nuclei involved in sensation, and their cortical projections, are discussed below.

Touch/Position sensation

Touch/position information from the body is sent to the ventral posterolateral nucleus (VPL) of the thalamus. Touch/position information from the face is sent to the ventral posteromedial nucleus (VPM) of the thalamus. From the VPL and VPM, information is projected to the primary sensory cortex (SI) in the postcentral gyrus of the parietal lobe.

The representation of sensory information in SI is organized somatotopically. Adjacent areas in the body are represented by adjacent areas in the cortex. When body parts are drawn in proportion to the density of their innervation, however, the result is a strangely distorted “little man,” the sensory homunculus.

Many textbooks reproduce the classic Penfield-Rasmussen diagram, which is now outdated. For example, the toes and genitals are shown in the classic diagram on the mesial surface of the cortex, when in fact they are represented on the convexity.[3] What is more important, the classic diagram implies a single primary sensory map of the body, when in fact there are multiple primary maps. At least four separate, anatomically-distinct sensory homunculi have been identified in SI. They represent different blends of input from surface receptors, deep receptors, rapidly adapting receptors, and slowly-adapting peripheral receptors. For example, smooth objects will activate certain cells, whereas edged objects will activate other cells.

Information from all four maps in the primary sensory cortex (SI) is sent to the secondary sensory cortex (SII) in the parietal lobe. SII contains two more sensory homunculi.

In general, information from one side of the body is represented on the opposite side in SI, but on both sides in SII. Functional MRI imaging of a defined stimulus (e.g., stroking the skin with a toothbrush) “lights up” a single focus in SI and two foci in SII.

Pain/Temperature sensation

Pain/temperature information is sent to the VPL (body) and VPM (face) of the thalamus (the same nuclei that receive touch/position information). From the thalamus, pain/temperature and touch/position information is projected onto SI.

In marked contrast to touch/position information, however, pain/temperature information is also sent to other thalamic nuclei, and is projected onto additional areas of the cerebral cortex. Some pain/temperature fibers are sent to the medial dorsal thalamic nucleus (MD), which projects to the anterior cingulate cortex. Other fibers are sent to the ventromedial (VM) nucleus of the thalamus, which projects to the insular cortex. Finally, some fibers are sent to the intralaminar (IL) nuclei of the thalamus via the reticular formation. The IL project diffusely to all parts of the cerebral cortex.

The insula and cingulate cortex are areas of the brain that represent our perception of touch/position and pain/temperature in the context of other simultaneous perceptions (sight, smell, taste, hearing and balance), and in the context of our memories and present emotional state. It is noteworthy that peripheral pain/temperature information is channeled directly into the brain at these deep levels, without prior processing. This contrasts markedly with the way that touch/position information is handled.

Diffuse thalamic projections from the IL and other thalamic nuclei are responsible for one’s overall level of consciousness. The thalamus and reticular formation “activate” the entire brain. It is noteworthy that peripheral pain/temperature information feeds directly into this system as well.

Summary

The complex processing of pain/temperature information in the thalamus and cerebral cortex (as opposed to the relatively simple, straightforward processing of touch/position information) reflects a phylogenetically older, more primitive sensory system. The rich, detailed information we receive from peripheral touch/position receptors is superimposed on a background of awareness, memory and emotions that is set, in part, by peripheral pain/temperature receptors.

The thresholds for touch/position perception are relatively easy to measure, and are similar in all humans. The thresholds for pain/temperature perception are difficult to define and even more difficult to measure. “Touch” is an objective sensation. “Pain” is a highly individualized, personal sensation that varies markedly among different people. It is conditioned by their memories and by their emotions. The fundamental anatomical differences between the pathways for touch/position perception and pain/temperature sensation help to explain why pain, especially chronic pain, is so difficult to manage.

Wallenberg syndrome

Wallenberg syndrome (also called the lateral medullary syndrome) is a classic clinical demonstration of the anatomy of the fifth nerve. It provides a useful summary of essential points about the processing of sensory information by the trigeminal nerve.

A stroke usually affects only one side of the body. If a stroke causes loss of sensation, the deficit will be lateralized to the right side or the left side of the body. The only exceptions to this rule are certain spinal cord lesions and the medullary syndromes, of which Wallenberg syndrome is the most famous example. In Wallenberg syndrome, a stroke causes loss of pain/temperature sensation from one side of the face and the other side of the body.

The explanation involves the anatomy of the brainstem. In the medulla, the ascending spinothalamic tract (which carries pain/temperature information from the opposite side of the body) is adjacent to the descending spinal tract of the fifth nerve (which carries pain/temperature information from the same side of the face). A stroke that cuts off the blood supply to this area (e.g., a clot in the posterior inferior cerebellar artery) destroys both tracts simultaneously. The result is loss of pain/temperature sensation (but not touch/position sensation) in a unique “checkerboard” pattern (ipsilateral face, contralateral body) that is entirely diagnostic.

See also

- Trigeminal neuralgia

- Cluster headache

- List of mnemonics for the cranial nerves

Notes

- ↑ Mnemonic at medicalmnemonics.com 38

- ↑ Butler AB, Hodos W. Comparative Vertebrate Neuroanatomy, 2nd ed. Wiley-Interscience, 2005.

- ↑ Kell CA, von Kriegstein K, Rösler A, Kleinschmidt A, Laufs H (2005). "The sensory cortical representation of the human penis: revisiting somatotopy in the male homunculus". J. Neurosci. 25 (25): 5984–7. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0712-05.2005. PMID 15976087. http://www.jneurosci.org/cgi/content/full/25/25/5984.

References

- Blumenfeld H. Neuroanatomy Through Clinical Cases. Sinauer Associates, Inc. 2002.

- Brodal A. Neurological Anatomy in Relation to Clinical Medicine, 3rd ed. Oxford University press, 1981.

- Brodal P. The Central Nervous System. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Carpenter MB, Sutin J. Human Neuroanatomy, 8th ed. Williams & Wilkins, 1983.

- DeJong, RN. The Neurologic Examination, 3rd ed. Hoeber, 1970.

- Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM. Principles of Neural Science, 4th ed. McGraw-Hill, 2000.

- Martin JH. Neuroanatomy Text and Atlas, 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2003.

- Patten J. Neurological Differential Diagnosis, 2nd ed. Springer, 1996.

- Ropper, AH, Brown RH. Adam’s and Victor’s Principles of Neurology, 8th ed. McGraw-Hill, 2001.

- Wilson-Pauwels, L, Akesson, EJ, Stewart, PA. Cranial Nerves: Anatomy and Clinical Comments. B. C. Decker Inc., 1998.

External links

- Pigeons Detect Magnetic Fields An experiment indicating that the trigeminal nerve, in the species Columba livia may be the mechanism through which "homing pigeons" detect magnetic fields

- cranialnerves at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (V)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||